Viviamo in un’epoca in cui la solitudine è onnipresente, ma raramente si manifesta per ciò che è. Una solitudine connessa, mascherata da notifiche, schermate lucide, conversazioni digitali che si dissolvono nel nulla. In questo contesto, leggere Il mestiere di vivere di Cesare Pavese può sembrare un gesto inattuale. Eppure, è proprio oggi che quelle pagine dure, spezzate, radicali, diventano un atto necessario. Un ritorno alla verità dell’essere umano, al coraggio di guardarsi dentro — anche quando fa male.

Un diario senza sconti

Il mestiere di vivere non è un libro pensato per il lettore. È il diario di un uomo che ha passato la vita a interrogarsi sul senso dell’esistere, dell’amare, dello scrivere. Pavese non cerca consolazioni: registra. Con lucidità spietata, annota il dolore, l’ossessione per la scrittura, le delusioni, l’incapacità di amare e quella di smettere di farlo. Fino all’estremo, fino a quel gesto finale — il suicidio, nell’agosto del 1950 — che non cancella le sue parole, ma le incide ancora più a fondo.

E proprio lì, nel punto più buio, può scattare la catarsi. Perché leggere Pavese oggi significa anche questo: riconoscere la propria fragilità e farne spazio vitale. Rendersi conto che vivere è un mestiere difficile, e che ammetterlo è già un modo per salvarsi.

La solitudine come verità, non come posa

Oggi siamo circondati da immagini che simulano intimità, da canzoni che parlano di cuori infranti in 3 minuti e 12 secondi, da storie da consumare e dimenticare. Ma tutto è spesso finto, tutto è superficie. Pavese, invece, va in profondità. E questa sua solitudine radicale, quella che lo porta al silenzio assoluto, diventa un paradossale inno alla vita: perché chi riesce a raccontare il dolore con questa precisione, in fondo, vuole ancora restare in contatto con ciò che è vivo.

In un tempo che anestetizza, Pavese urla. E quel grido, che ci arriva da un secolo fa, può servirci oggi come risveglio interiore, come invito a fermarci e riconnetterci davvero, senza filtri.

L’arte vera nasce dal conflitto

C’è un’altra lezione che Il mestiere di vivere ci consegna, ed è sul fare arte. In un mondo in cui tutto deve essere facile, vendibile, virale, Pavese ci ricorda che la creazione artistica è un processo faticoso, a volte doloroso, mai automatico. “Soffrire è l’unico modo per essere profondi”, sembra dirci. Non per masochismo, ma per rigore.

Oggi, molta produzione artistica — dalla musica alle serie TV, dai romanzi ai post — vive nel loop del “già sentito”, della replica estetica, della forma priva di tensione. Pavese, con il suo scrivere asciutto e incandescente, ci riporta a un’altra idea di arte: non un rifugio, ma un campo di battaglia. Non intrattenimento, ma necessità.

Scrivere per non morire: Pavese e la parola come resistenza

Nel diario, la scrittura per Pavese non è mai semplice espressione. È uno sforzo, una fatica, una condanna e insieme una salvezza. Ogni pagina è attraversata dalla tensione tra il bisogno di scrivere e la consapevolezza che la parola non basta, che non salva davvero. Eppure, continua. Scrive ogni giorno, in modo disciplinato, perché non scrivere sarebbe peggio.

In questo, c’è una forma di resistenza che oggi possiamo sentire fortissima. In un tempo in cui le parole sono inflazionate, gettate a caso nei social, riutilizzate senza pensiero, Pavese ci obbliga a confrontarci con la parola come gesto responsabile. Scrivere è vivere, per lui, anche quando vivere è impossibile.

E forse anche per noi, oggi, scrivere (un diario, una poesia, una lettera) può diventare una forma di cura, un modo per riappropriarci del nostro sentire — senza filtri, senza pubblico, solo con onestà.

(Ri)leggere Pavese per ritrovare sé stessi

Non è un libro facile Il mestiere di vivere, né vuole esserlo. Ma è un libro vero. Rileggerlo oggi non significa inseguire la malinconia o glorificare il dolore, ma scegliere un’altra via: quella della consapevolezza. In tempi confusi, può essere un atto di resistenza leggere un diario che non mente, che non consola, che non cerca like.

E magari, nel gesto silenzioso di aprire quelle pagine, qualcuno ritroverà non solo Pavese, ma anche una parte dimenticata di sé.

"Non si ricordano i giorni, si ricordano gli attimi."

E forse, Il mestiere di vivere può ancora regalarci attimi autentici. Attimi in cui tornare a sentirsi vivi.

The Business of Living Today: Pavese, Solitude, and the Truth of Art

We live in an age where solitude is omnipresent, yet rarely revealed for what it truly is. It’s a connected kind of solitude, masked by notifications, glossy screens, and digital conversations that vanish into nothingness. In this context, reading The Business of Living by Cesare Pavese may seem anachronistic. And yet, it is precisely now that those harsh, fractured, radical pages feel necessary. A return to the truth of being human, to the courage of looking inward — even when it hurts.

A Diary Without Concessions

The Business of Living is not a book written for readers. It is the diary of a man who spent his life questioning the meaning of existence, love, and writing. Pavese seeks no comfort: he records. With ruthless clarity, he notes pain, his obsession with writing, disappointments, his inability to love — and to stop loving. All the way to the extreme, to that final act — his suicide in August 1950 — which does not erase his words but carves them even deeper.

And right there, in that darkest point, a kind of catharsis may occur. Because reading Pavese today means recognizing our own fragility and making space for it. Realizing that living is a difficult craft — and that admitting it is already a way to survive.

Solitude as Truth, Not Pose

We are surrounded by images simulating intimacy, by songs about broken hearts that last 3 minutes and 12 seconds, by stories designed to be consumed and forgotten. But most of it is fake, all surface. Pavese, instead, goes deep. And his radical solitude — the kind that leads to absolute silence — becomes, paradoxically, a hymn to life: because anyone who can describe pain with such precision still longs to stay connected to what is alive.

In a time that anesthetizes, Pavese screams. And that scream, echoing from a century ago, can serve today as a call to inner awakening, an invitation to pause and truly reconnect, without filters.

Real Art Is Born of Conflict

There’s another lesson The Business of Living leaves us with: one about making art. In a world where everything must be easy, sellable, and viral, Pavese reminds us that artistic creation is a demanding, often painful process — never automatic. “Suffering is the only way to be profound,” he seems to say. Not out of masochism, but from discipline.

Much of today’s artistic output — from music to TV series, from novels to social posts — exists in a loop of déjà vu, aesthetic repetition, and tensionless form. Pavese, with his dry and burning prose, brings us back to another idea of art: not a refuge, but a battlefield. Not entertainment, but necessity.

Writing to Stay Alive: Pavese and the Word as Resistance

In his diary, writing is never just self-expression. It’s effort, burden, both a curse and a lifeline. Every page is marked by the tension between the need to write and the knowledge that words are not enough — that they do not truly save. And yet, he persists. He writes every day, with discipline, because not writing would be worse.

In this, there is a form of resistance we can still feel deeply today. In a time when words are cheapened, thrown casually onto social media, recycled without thought, Pavese forces us to face the word as a responsible act. For him, writing is living — even when living is impossible.

And maybe, even for us today, writing (a diary, a poem, a letter) can become a form of healing — a way to reclaim our inner world. Unfiltered, unperformed, simply honest.

(Re)Reading Pavese to Find Ourselves

The Business of Living is not an easy book, nor does it wish to be. But it is a true one. To reread it today is not about chasing melancholy or romanticizing pain — it’s about choosing another path: that of awareness. In confusing times, it can be an act of resistance to read a diary that doesn’t lie, doesn’t console, and doesn’t seek approval.

And perhaps, in the silent act of opening those pages, someone may find not only Pavese — but also a forgotten part of themselves.

"We do not remember days, we remember moments."

And perhaps The Business of Living still has moments to offer — moments that make us feel alive again.

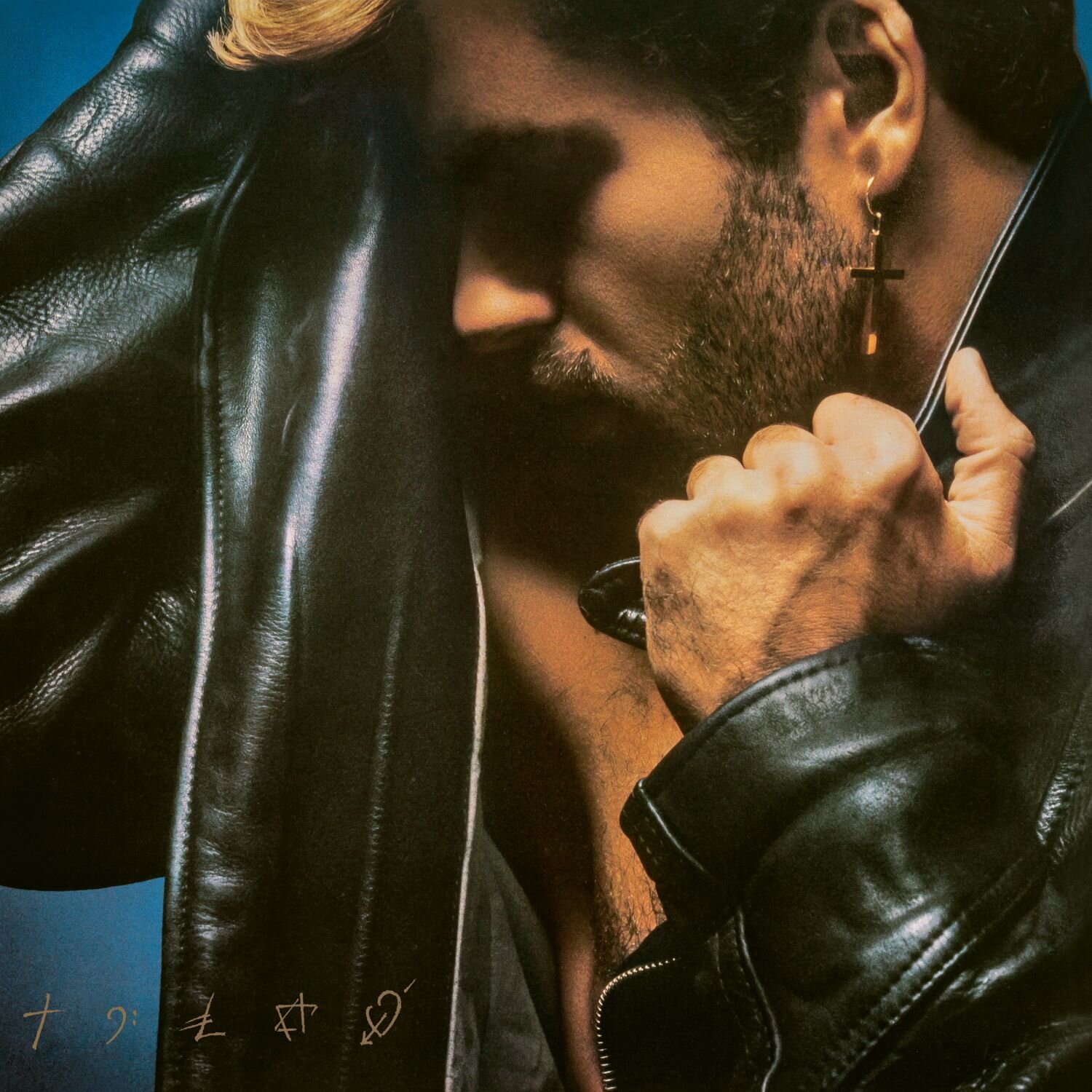

Photo credits Poligrafici Editoriale S.p.A., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons