Il cinema è morto, ci racconta Franco Maresco in Un film fatto per Bene, arrivato a chiudere l’82ª Mostra internazionale d’arte cinematografica di Venezia. Ma proprio la sua presenza, la sua forza, la sua esistenza stessa, testimonia l’esatto contrario. Il cinema vive, perché ha ancora autori capaci di disturbare, di ridere del nulla, di scarnificare la realtà fino a renderla insopportabile e irresistibile. Anche grazie a produttori illuminati come Andrea Occhipinti di Lucky Red – figura che nel film diventa quasi co-protagonista – possiamo assistere a un’opera che si annuncia già come cult.

Maresco parte dall’ossessione per Carmelo Bene, genio inafferrabile che ha inseguito per anni, ma il film che avrebbe dovuto raccontarlo si sgretola sotto i nostri occhi. E così, più che un’opera “su Bene”, Un film fatto per Bene diventa un viaggio dentro Maresco stesso: i suoi incubi, le sue ossessioni, la sua ferocia nel dire che il cinema italiano è morto. Nessuno si salva: critici, attori, produttori, spettatori. Tutti inchiodati da un sarcasmo spietato.

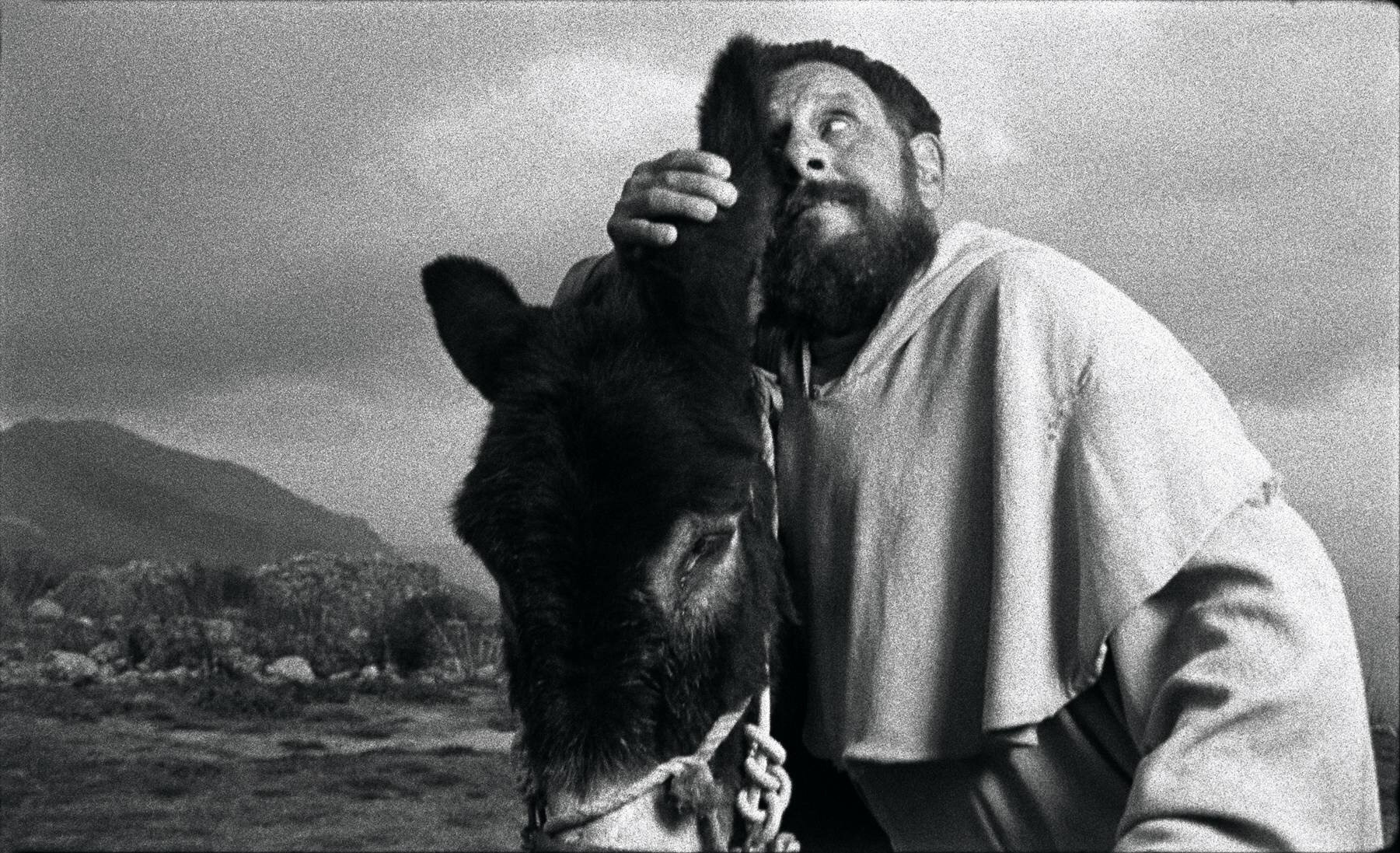

Ma, come sempre con Maresco, la disperazione convive con l’umorismo. Lo vediamo dichiararsi “il Carmelo Bene del XXI secolo”, con frasi fulminanti e rituali maniacali che sono tanto tragici quanto irresistibili. Lo vediamo scomparire, lasciare il set, diventare fantasma della propria stessa opera. Nel frattempo, Umberto Cantone, amico e sceneggiatore, lo insegue per Palermo come in una detective story surreale, incontrando amici, collaboratori, tassisti devoti e un’umanità terminale che sembra uscita dalle visioni di Cinico Tv.

C’è la lunga, tombale carrellata sulle lapidi del cimitero – sequenza che poteva chiudere il film lasciandoci senza speranza – e invece accade l’imprevisto: Maresco si solleva insieme al suo Santo Volante. Non è soltanto un volo, ma un’ascensione ironica e struggente, una sospensione nell’aria che porta con sé la leggerezza del paradosso. Sorvolano Palermo come due cavalieri disallineati, con lo sguardo che dall’alto sembra cercare un frammento di senso nelle macerie del reale. È qui, tra le nuvole, che si apre uno spiraglio: la possibilità che la speranza non stia nei grandi sistemi, ma nella gioia minuta, ostinata, delle piccole cose.

Un film fatto per Bene è dissacrante, esilarante, funereo, eppure incredibilmente vitale. È un requiem che diventa rinascita, un corteo funebre che all’improvviso si solleva in aria. Ma soprattutto è un atto di devozione al genio di Carmelo Bene: la sua voce che spezza il linguaggio, la sua ironia che abbatte ogni certezza, il suo genio che confonde realtà e illusione fino a renderle indistinguibili. In questo continuo oscillare tra vero e falso, tra sacro e grottesco, Maresco ci regala la possibilità di un’altra visione: fuggire dal reale non per negarlo, ma per scoprire che forse l’unica verità possibile è proprio nell’illusione.

Alla fine rimane la domanda: davvero il cinema è morto? Forse sì, se pensiamo all’industria, alle produzioni senz’anima, alla tecnologia che livella tutto. Ma se ancora può esistere un film come questo, capace di irritare, divertire, commuovere e far pensare, allora il cinema è vivo. È vivo nella sua capacità di scuoterci, di sorprenderci, di farci sentire, ancora una volta, Bene.

A Film Made for Bene: Franco Maresco and the Impossible Resurrection of Cinema

Cinema is dead, Franco Maresco tells us in A Film Made for Bene, which closed the 82nd Venice International Film Festival. And yet, its very presence, its strength, its sheer existence, testify to the exact opposite. Cinema lives, because there are still filmmakers capable of disturbing, of laughing at nothingness, of stripping reality bare until it becomes unbearable and irresistible. Thanks also to enlightened producers such as Andrea Occhipinti of Lucky Red – who in the film almost becomes a co-protagonist – we can witness a work already destined to become a cult.

Maresco begins with his obsession for Carmelo Bene, the elusive genius he chased for years, but the film that was supposed to tell his story falls apart before our eyes. And so, more than a work “about Bene,” A Film Made for Bene becomes a journey inside Maresco himself: his nightmares, his obsessions, his ferocity in declaring that Italian cinema is dead. No one is spared: critics, actors, producers, spectators. All nailed down by merciless sarcasm.

But, as always with Maresco, despair coexists with humor. We see him proclaiming himself “the Carmelo Bene of the 21st century,” with witty remarks and maniacal rituals that are both tragic and irresistible. We see him vanish, abandon the set, become the ghost of his own work. Meanwhile, Umberto Cantone, friend and screenwriter, chases him through Palermo like in a surreal detective story, encountering friends, collaborators, devoted taxi drivers, and a terminal humanity that seems straight out of the visions of Cinico Tv.

There is the long, tomb-like tracking shot over the gravestones in the cemetery – a sequence that could have ended the film by leaving us without hope – and then the unexpected happens: Maresco rises together with his Flying Saint. It is not merely a flight, but an ironic and poignant ascension, a suspension in the air that carries with it the lightness of paradox. They fly over Palermo like two misaligned knights, with a gaze that from above seems to search for a fragment of meaning in the ruins of the real. And here, among the clouds, a crack opens: the possibility that hope does not lie in grand systems, but in the small, stubborn joy of little things.

A Film Made for Bene is irreverent, hilarious, funereal, and yet incredibly vital. It is a requiem that becomes a rebirth, a funeral procession that suddenly takes flight. Above all, it is an act of devotion to the genius of Carmelo Bene: his voice that shatters language, his irony that demolishes every certainty, his genius that blurs reality and illusion until they become indistinguishable. In this constant oscillation between truth and falsehood, between the sacred and the grotesque, Maresco offers us the possibility of another vision: escaping reality not to deny it, but to discover that perhaps the only possible truth lies precisely in illusion.

In the end, the question remains: is cinema really dead? Perhaps yes, if we think of the industry, the soulless productions, the technology that flattens everything. But if a film like this can still exist, capable of irritating, amusing, moving, and making us think, then cinema is alive. Alive in its ability to shake us, to surprise us, to make us feel, once again, Bene.