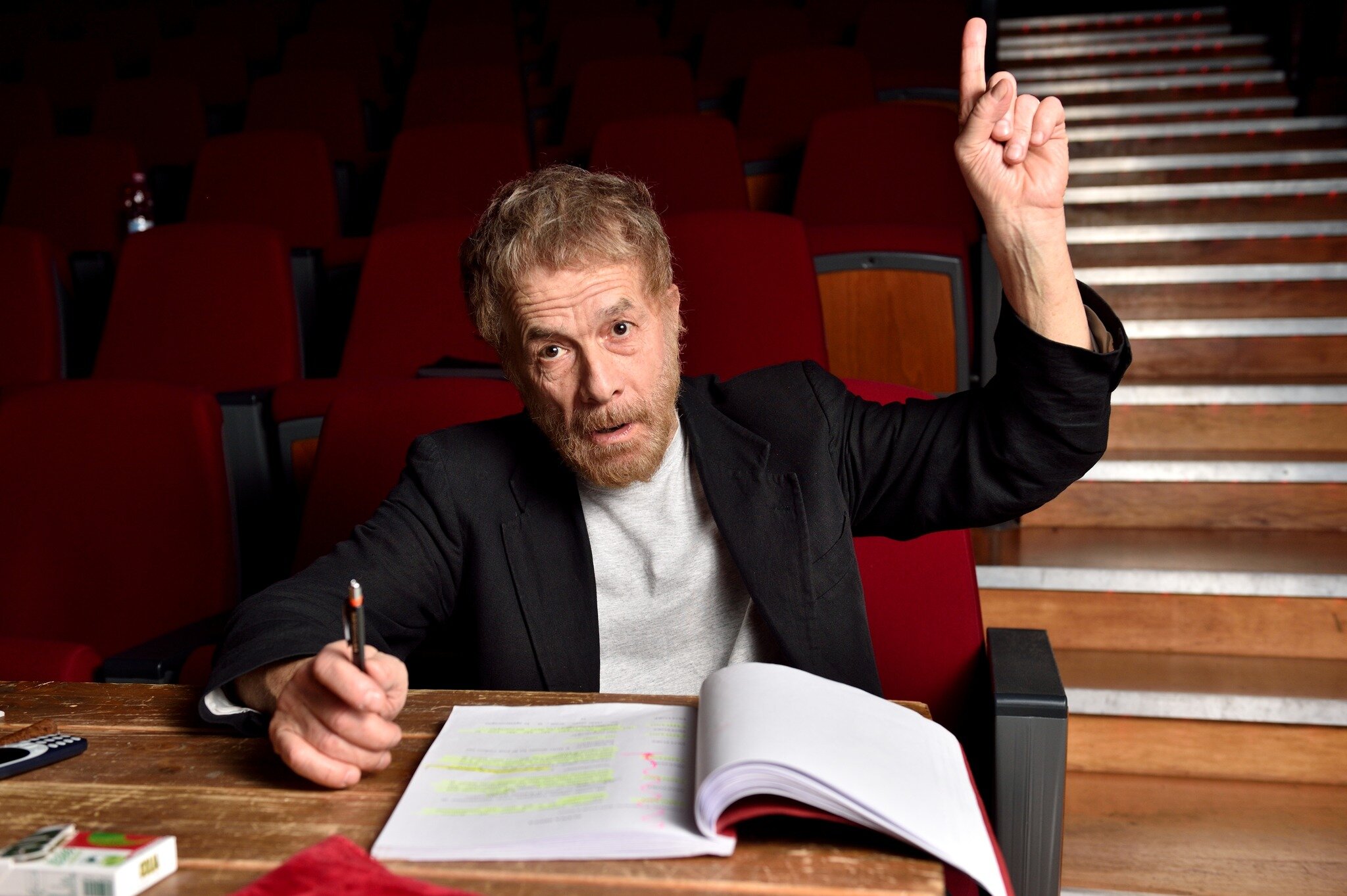

Cinquant’anni dopo Profondo Rosso, il ritratto di un indocile del teatro italiano

Cinquant’anni fa, nel 1975, un giovane attore dagli occhi inquieti compariva in Profondo Rosso di Dario Argento. La sua figura, tagliata in controluce tra ombra e riflesso, aveva già qualcosa di diverso: la densità di chi porta sulla pelle un’inquietudine che non si spegne mai. Per Gabriele Lavia, quel film non fu un traguardo ma una deviazione momentanea. La sua vera dimora, il suo campo di battaglia, era altrove: nel teatro, luogo sacro e terreno di fatica, dove ogni gesto pesa come una parola.

Oggi, a ottantatré anni, Lavia continua a recitare, dirigere, pensare. È rimasto uno dei pochi a difendere la purezza del palcoscenico, la sua verità fragile e indomabile. C’è in lui qualcosa di arcaico e di moderno insieme: la severità di chi crede nel mestiere e la libertà di chi si sa insubordinato. Non per ribellione sterile, ma per necessità. Perché l’arte, se vuole restare viva, deve disobbedire.

Le sue radici affondano in una geografia complessa. Nato a Milano da genitori siciliani, cresciuto a Torino, scopre la vocazione da bambino, a Catania, davanti alle rappresentazioni dei Filodrammatici. È lì che intuisce che il teatro non è finzione ma destino. Quando, da giovane, comunica al padre di voler fare l’attore, il gesto viene vissuto come un tradimento. Eppure, quella frattura diventa il primo atto di libertà, il passo necessario per diventare se stesso.

Alla fine degli anni Sessanta studia all’Accademia d’Arte Drammatica di Roma, formandosi accanto a due maestri che segneranno per sempre il suo cammino: Orazio Costa e Giorgio Strehler. Da loro impara che l’attore non è un interprete, ma uno strumento al servizio di una forma più grande. E che la scena non tollera approssimazione. Tutto deve essere studiato, costruito, interiorizzato. La verità non nasce dal caso, ma dall’armonia invisibile che governa il movimento, il ritmo, lo spazio.

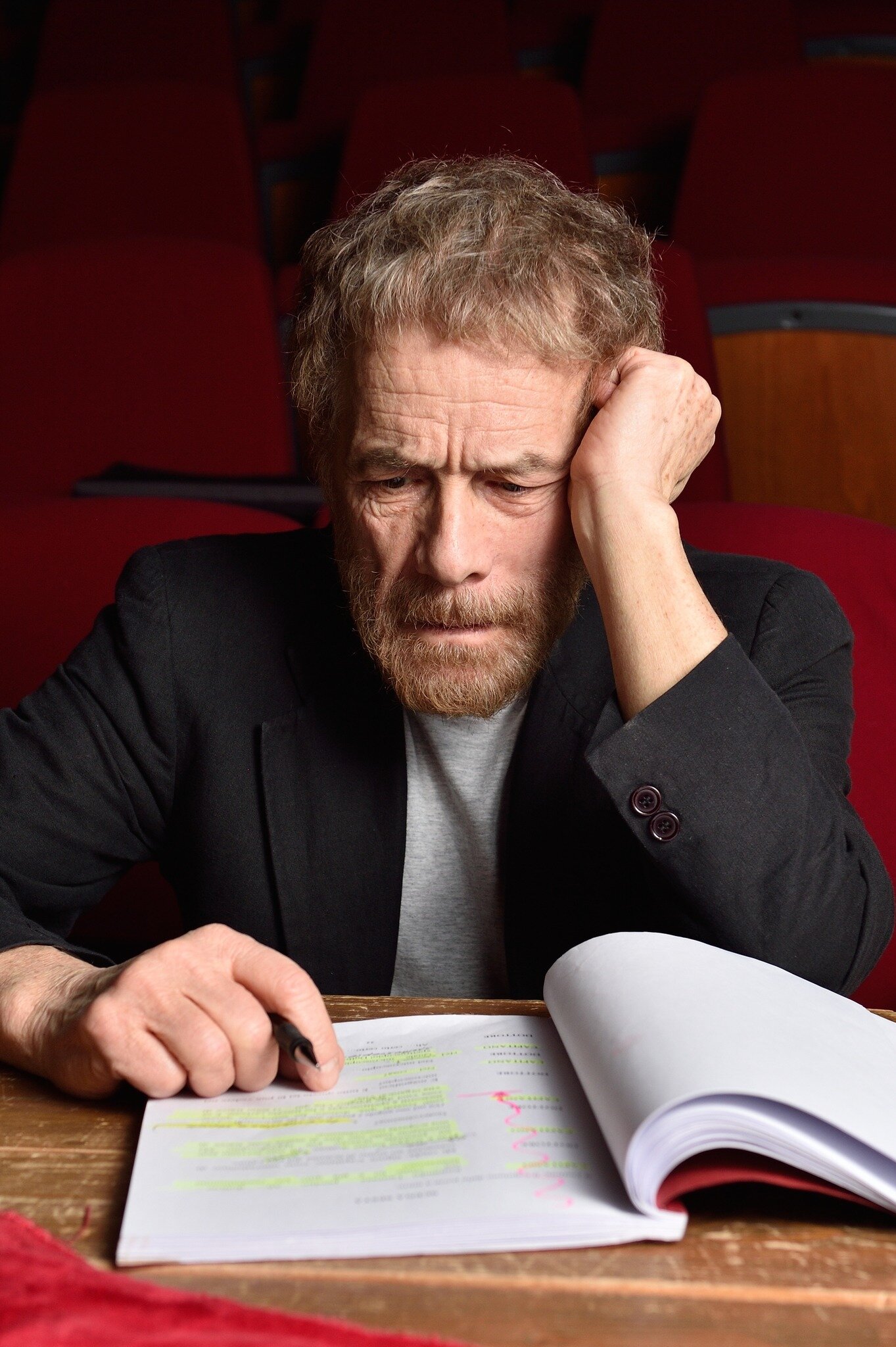

Lavia porta questa idea con sé per tutta la vita. Nel suo teatro nulla è lasciato al disordine: ogni gesto è parte di una geometria segreta, ogni silenzio ha un peso, ogni luce ha un senso. È un’idea antica e allo stesso tempo rivoluzionaria. Il suo rigore non ha nulla di accademico: è una forma d’amore. Amore per il mestiere, per la parola, per quel mistero di equilibrio che trasforma la tecnica in emozione.

Negli anni, attraversa Shakespeare, Pirandello, Strindberg, Goldoni, O’Neill. Fonda la sua compagnia, dirige teatri e festival, diventa riferimento e maestro per generazioni di attori. Ma resta, in fondo, un artigiano solitario, uno che costruisce con mani e voce. Quando affronta testi come Re Lear o Lungo viaggio verso la notte, lo fa come se ogni battuta fosse un frammento di sé, una confessione più che una recita. Dentro quei ruoli estremi si misura con la vecchiaia, con la perdita, con la memoria: un uomo che si interroga, più che un attore che interpreta.

Eppure, nonostante tutto, Lavia rifugge qualsiasi autocompiacimento. Non parla di carriera, né di successo. Preferisce il dubbio, la disciplina, lo studio quotidiano. Il suo teatro nasce da un’idea semplice e spietata: che l’incanto non si improvvisa, ma si conquista con fatica. Innovare, per lui, non significa rompere le regole, ma conoscerle così a fondo da superarle con grazia.

Oggi, guardandolo in scena, si ha l’impressione di assistere a un rito antico: la voce che si fa corpo, il gesto che diventa memoria, il respiro che unisce attore e pubblico in un tempo sospeso. Lavia sembra ancora cercare qualcosa di irriducibile, come se ogni spettacolo fosse un atto di resistenza contro la superficialità e il rumore del presente.

Negli ultimi anni, riflettendo sul proprio percorso, ha parlato spesso della vecchiaia come di un territorio difficile, quasi ostile. Ma non c’è rassegnazione nelle sue parole, piuttosto una forma di rabbia vitale, di lucidità ferita. Continua a studiare, a lavorare, a interrogarsi sul senso di questo mestiere che consuma e salva insieme. Forse è proprio in quella tensione che si rivela il suo segreto: l’arte come disciplina, la disciplina come forma d’amore.

Cinquant’anni dopo Profondo Rosso, Gabriele Lavia non è il volto di un film di culto, ma la memoria viva di un’idea di teatro che resiste. Crede ancora che l’arte debba restituire all’uomo un’immagine di sé, e che la scena, in fondo, sia il luogo dove il reale e il possibile si toccano per un istante.

Nel suo modo di stare in scena, severo e insieme vulnerabile, si sente il peso del tempo e la leggerezza di chi non ha smesso di credere nella necessità dell’arte.

Forse il teatro, per Lavia, è proprio questo: l’ostinazione di continuare a cercare la verità nel buio, anche quando il mondo sembra aver dimenticato dove guardare.

Gabriele Lavia: Art as a Discipline of the Soul

(Fifty years after Deep Red, the portrait of an unruly master of Italian theatre)

Fifty years ago, in 1975, a young actor with restless eyes appeared in Deep Red by Dario Argento. His figure, cut in backlight between shadow and reflection, already had something different about it: the density of someone who carries an unease that never fades. For Gabriele Lavia, that film was not a milestone but a temporary detour. His true home, his battlefield, was elsewhere — in the theatre, that sacred place and field of labor where every gesture weighs as much as a word.

Today, at eighty-three, Lavia continues to act, direct, and think. He remains one of the few who still defends the purity of the stage — its fragile, untamed truth. There is something both archaic and modern about him: the severity of one who believes in the craft, and the freedom of one who knows he is insubordinate. Not out of sterile rebellion, but out of necessity. Because art, if it wants to stay alive, must disobey.

His roots lie in a complex geography. Born in Milan to Sicilian parents, raised in Turin, he discovered his vocation as a child in Catania, watching the performances of the local Filodrammatici. It was there that he understood theatre was not fiction, but destiny. When, as a young man, he told his father he wanted to become an actor, the gesture was seen as a betrayal. Yet that fracture became his first act of freedom — the necessary step toward becoming himself.

In the late 1960s, he studied at the National Academy of Dramatic Arts in Rome, learning under two masters who would shape his path forever: Orazio Costa and Giorgio Strehler. From them he learned that an actor is not a mere interpreter, but an instrument in service of a greater form. And that the stage allows no approximation. Everything must be studied, built, internalized. Truth does not arise by chance, but from the invisible harmony that governs movement, rhythm, and space.

Lavia has carried this idea with him throughout his life. In his theatre, nothing is left to disorder: every gesture belongs to a secret geometry, every silence has weight, every light has meaning. It is an idea both ancient and revolutionary. His rigor has nothing academic about it — it is a form of love. Love for the craft, for the word, for that mysterious balance that turns technique into emotion.

Over the years, he has traversed Shakespeare, Pirandello, Strindberg, Goldoni, and O’Neill. He founded his own company, directed theatres and festivals, and became a reference and mentor for generations of actors. Yet he remains, at heart, a solitary craftsman — one who builds with hands and voice, who sees theatre as an exact science of the soul.

When he takes on roles like King Lear or Long Day’s Journey into Night, he approaches them as if every line were a fragment of himself — a confession more than a performance. Within those extreme roles, he wrestles with age, loss, and memory: a man questioning himself, rather than an actor interpreting.

And yet, despite everything, Lavia avoids any self-indulgence. He does not speak of career or success. He prefers doubt, discipline, daily study. His theatre is born from a simple, merciless idea: that enchantment cannot be improvised, but must be earned through labor. To innovate, for him, does not mean breaking the rules — it means knowing them so deeply that one can transcend them with grace.

Today, watching him on stage, one has the impression of witnessing an ancient ritual: the voice becoming body, the gesture becoming memory, the breath uniting actor and audience in a suspended time. Lavia still seems to be searching for something irreducible, as if every performance were an act of resistance against the superficiality and noise of the present.

In recent years, reflecting on his own journey, he has often spoken of old age as a difficult, almost hostile territory. But there is no resignation in his words — rather a form of vital anger, of wounded lucidity. He continues to study, to work, to question the meaning of this craft that consumes and redeems at once. Perhaps it is in that tension that his secret lies: art as discipline, and discipline as a form of love.

Fifty years after Deep Red, Gabriele Lavia is not the face of a cult film, but the living memory of an idea of theatre that endures. He still believes that art must give humanity back an image of itself, and that the stage, ultimately, is the place where the real and the possible touch for an instant.

In his way of being on stage — severe yet vulnerable — one can feel both the weight of time and the lightness of someone who has never stopped believing in the necessity of art. Perhaps theatre, for Lavia, is precisely this: the stubbornness of continuing to seek truth in the dark, even when the world seems to have forgotten where to look.

Ph Filippo Manzini