Scrivere di Ornella Vanoni oggi, nel momento in cui il suo corpo non abita più la scena ma la sua impronta è impressa ovunque mette un certo brivido. Non perché manchino le parole, anzi: il web è già pieno di biografie, tributi, ricostruzioni meticolose di una carriera monumentale. Raccontare tutto sarebbe un’impresa da archivisti, e non è questo il mio intento.

Quello che cerco, piuttosto, è un’altra angolatura: non il profilo definitivo, ma una piccola monografia personale, un modo di attraversare la sua arte così come l’ho incontrata io nel tempo, a volte in ritardo, spesso senza capirla, poi con crescente amore.

Per quelli come me, nati sul finire dei Sessanta e con l’adolescenza che arrivava insieme agli ultimi lampi dei Settanta, Ornella era “musica da vecchi”. O almeno così ci sembrava allora, mentre alla porta bussavano il Punk dei Sex Pistols e Roxanne dei Police iniziava a girare nelle radio come un segnale di nuovi mondi possibili.

Non capivamo, non potevamo capire, la sua sensualità adulta, la sua eleganza sfrontata, quella femminilità che sfuggiva alle categorie. Lei aveva quarant’anni, poi cinquanta: un’età che allora mi sembrava remota. L’ho capita solo quando ci sono arrivato anch’io, accorgendomi che proprio in quella stagione della vita Ornella era un miracolo: bellissima, libera, sensuale, naturalmente erotica, perfettamente compiuta.

Tutti abbiamo un ricordo personale legato a Ornella. Il mio è custodito in un disco che, ad ogni ascolto, continua a sembrarmi un’opera incompiuta, ma decisamente affascinante: Io dentro – Io fuori. Un lavoro a tratti bizzarro, troppo avanti per essere capito del tutto, troppo imperfetto per essere amato davvero dal grande pubblico, troppo sincero per essere dimenticato. Nel mezzo di pezzi straordinari convivono canzoni meno fortunate, quasi degli incidenti di percorso che però contribuiscono a consegnare al disco un’aura sghemba, volutamente sbilenca, tipicamente anni Settanta.

Inciso con i New Trolls, quel progetto sopravvive come un reperto prezioso della nostra storia musicale. La tournée che ne seguì fu un successo pieno, eppure il suo ricordo è sfuggente: cercando oggi, perfino su YouTube, resta pochissimo, quasi niente. Qualche frammento da “Ma che sera” di Raffaella Carrà, qualche scampolo di immagini di una stagione che pare essere stata inghiottita dal tempo.

Io dentro – Io fuori

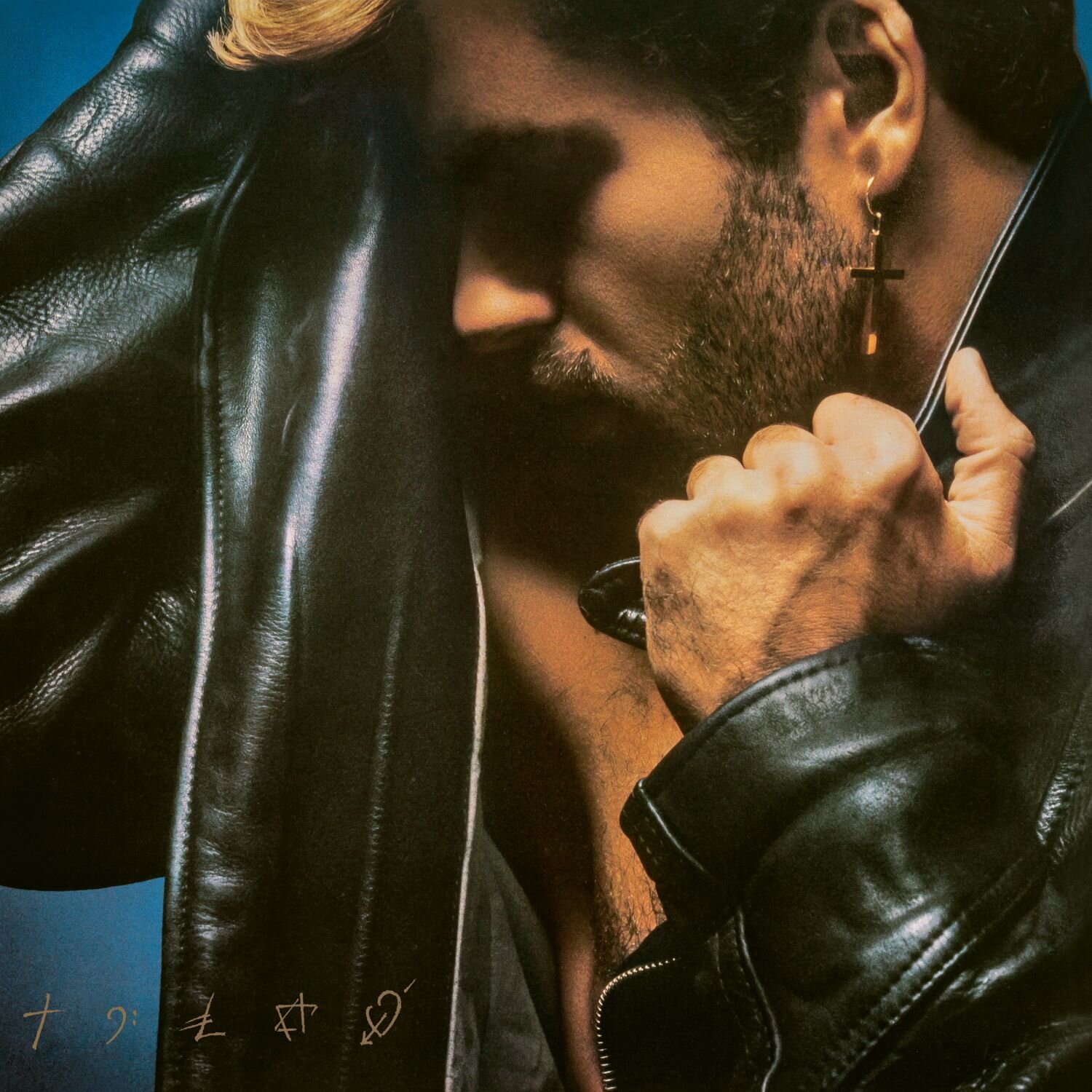

Io dentro – Io fuori nasce nel 1977 come un oggetto strano, volutamente eccentrico, a partire dalla copertina. Ornella gioca con maschere, clown, travestimenti, in una composizione sofisticata immaginata da Mauro Balletti: è già una dichiarazione d’intenti. L’eleganza si mescola al grottesco, la leggerezza al teatro. È un album che non vuole farsi prendere sul serio e allo stesso tempo pretende una serietà assoluta.

A distanza di un solo anno da La voglia, la pazzia, l’incoscienza, l’allegria, il capolavoro brasiliano con Vinícius e Toquinho, la Vanoni decide di spiazzare tutti. Invece di replicare un successo internazionale, fa una sterzata. E va a bussare ai New Trolls in un momento per loro di pieno rilancio: arrangiamenti complessi, armonie fitte, un gusto pop progressivo che aveva poco a che fare con la sua tradizione melodica.

Il risultato è un doppio album irregolare, vivo, pieno di tentativi e ripensamenti, che sembra quasi mettere in scena la tensione di un’artista che vuole reinventarsi. Io dentro è la parte più introversa, fatta di confessioni a bassa voce, tinte soul, pulsazioni intime. Io fuori è l’esatto contrario: una corsa libera tra funk, disco, seduzione esplicita. Ornella, in mezzo, si muove come un’attrice che cambia costume venti volte, senza mai perdere il fuoco.

Non tutti i brani sono perfetti e forse è proprio lì che sta il fascino del progetto. Alcuni pezzi portano in sé un entusiasmo spavaldo, altri una certa ingenuità anni Settanta, ma il tutto è percorso da una coerenza sotterranea: l’amore, visto nelle sue contraddizioni più radicali. Amore come specchio, amore come resa, amore come teatro.

Ci sono i due splendidi omaggi a Chico Buarque — Tatuaggio e Occhi negli occhi — tradotti da Bardotti, con quella capacità del brasiliano di rendere la malinconia un atto politico. Ci sono i momenti in cui i New Trolls avvolgono la voce della Vanoni con incastri vocali quasi cerebrali. E poi c’è Ti voglio: sei minuti di malizia, archi, falsetti, ironia, il tutto condito in salsa disco music che oggi sembrano predire l’arrivo dell’electro-pop italiano di vent’anni dopo.

L’intero progetto uscì sia come doppio che come disco singolo, come se già allora non ci fosse un solo modo possibile di ascoltarlo. E forse è vero ancora oggi: è un album che si lascia leggere da angolazioni diverse, mai definitivo, mai immobilizzato in una sola interpretazione.

La suggestione di “Avere vent’anni”

A complicare ulteriormente la storia di questo album così eccentrico c’è un cortocircuito culturale che dice molto dell’Italia di quegli anni. Due brani di Io dentro – Io fuori, Noi e Ti voglio, finiscono infatti nella colonna sonora del film più censurato, più tagliato, più rimosso del nostro immaginario collettivo: Avere vent’anni di Fernando Di Leo.

Un film che oggi è un oggetto di culto ma che all’epoca fu accolto come un corpo estraneo, disturbante, indecente. Le sue protagoniste, Lilli Carati e Gloria Guida, attraversano un’Italia stanca, violenta, incapace di guardare davvero al proprio futuro. E dentro quella storia di libertà negata, la voce di Ornella arriva come una promessa ingenua e tragica insieme.

È un dettaglio quasi nascosto nella sua discografia, eppure dice tutto: la Vanoni non è mai stata un’artista da rassicurazioni. Anche quando sembrava perfettamente integrata nel mainstream, era sempre un passo più avanti, più laterale, più coraggiosa.

Ritrovare oggi Io dentro-Io fuori

Riascoltare oggi Io dentro – Io fuori significa accostarsi a un’Ornella meno ovvia, meno levigata, più vulnerabile e più audace. Una Vanoni che non cerca la perfezione, che non teme le sbavature perché nelle sbavature, spesso, si annida la vita.

È un disco che permette di vederla da un’angolatura diversa: non la diva impeccabile, non l’icona popolare, ma la donna che attraversa le proprie contraddizioni senza farsene travolgere. Una donna che, anche nelle sue fragilità, ha saputo trasformare tutto: dolore, gioia, cadute, rinascite, in una forma di bellezza.

Negli ultimi anni Ornella aveva imparato a raccontarsi con una sincerità quasi disarmante, come se ogni ricordo fosse un frammento da consegnare al mondo prima che si dissolvesse. Parlava della sua vita come di un intreccio complesso, duro e luminoso, e in quelle parole c’era la stessa energia che attraversa questo album del ’77: la consapevolezza di aver vissuto tutto, di aver sentito tutto, di non essersi risparmiata nulla.

Forse è anche per questo che Io dentro – Io fuori merita di essere riascoltato oggi. Perché dentro quelle canzoni si trova una Vanoni che sfugge alle etichette, che gioca, rischia, osa, e che proprio per questo continua a parlarci. Una Vanoni completa, imperfetta, magnifica. Che ci ricorda, ancora una volta, che Ornella è stata davvero tutto e tutto ha saputo restituire.

Rediscovering Ornella Vanoni through Io dentro – Io fuori

Writing about Ornella Vanoni today, at a moment when her body no longer inhabits the stage but her imprint is everywhere, gives a certain shiver. Not because words are lacking—in fact, the web is already full of biographies, tributes, meticulous accounts of a monumental career. To tell everything would be an archivist’s task, and that is not my aim.

What I am looking for, instead, is another angle: not the definitive profile, but a small personal monograph, a way of experiencing her art as I encountered it over time, sometimes late, often without fully understanding it, and then with growing love.

For those like me, born in the late Sixties with adolescence arriving alongside the last flashes of the Seventies, Ornella was “old people’s music.” Or at least that’s how it seemed back then, while punk from the Sex Pistols was pounding at the door and Roxanne by The Police began spinning on the radio as a sign of new worlds opening up.

We didn’t understand—couldn’t understand—her adult sensuality, her brazen elegance, that femininity that escaped any category. She was in her forties, then her fifties: an age that felt remote to me then. I understood it only when I got there myself, realizing that precisely in that season of life Ornella was a miracle: beautiful, free, sensual, naturally erotic, perfectly formed.

We all have a personal memory tied to Ornella. Mine is kept in a record that, with every listen, still feels like an unfinished work, yet undoubtedly fascinating: Io dentro – Io fuori. A record at times bizarre, too ahead of its time to be fully understood, too imperfect to be truly loved by the mainstream, too sincere to be forgotten. Amid extraordinary tracks, less fortunate songs coexist—almost missteps, yet capable of giving the album its crooked, deliberately off-balance, unmistakably Seventies aura.

Recorded with the New Trolls, that project survives as a rare artifact of our musical history. The tour that followed was a real success, yet its memory is elusive: searching today, even on YouTube, very little remains. A few fragments from Raffaella Carrà’s “Ma che sera,” a handful of fleeting images from a season seemingly swallowed by time.

Io dentro – Io fuori

Io dentro – Io fuori was born in 1977 as a strange, deliberately eccentric object, starting with the cover. Ornella plays with masks, clowns, disguises, in a sophisticated composition imagined by Mauro Balletti: already a statement of intent. Elegance mixes with the grotesque, lightness with theatre. It’s an album that refuses to be taken lightly and yet demands absolute seriousness.

Just one year after La voglia, la pazzia, l’incoscienza, l’allegria—the Brazilian masterpiece with Vinícius and Toquinho—Vanoni chooses to surprise everyone. Instead of replicating an international success, she takes a sharp turn. And she knocks on the door of the New Trolls, at a time when the band was experiencing a full revival: complex arrangements, dense harmonies, a progressive pop flavor far removed from her melodic tradition.

The result is an irregular, energetic double album, full of attempts and second thoughts, almost staging the tension of an artist determined to reinvent herself. Io dentro is the more introspective side, filled with whispered confessions, soul tinges, intimate pulses. Io fuori is the opposite: a free run through funk, disco, explicit seduction. Ornella moves between the two like an actress changing costume twenty times, without ever losing her fire.

Not all tracks are perfect—and perhaps that’s where the project’s charm lies. Some pieces carry a bold enthusiasm, others a certain Seventies naïveté, yet the entire work is threaded with an underground coherence: love in its most radical contradictions. Love as mirror, love as surrender, love as theatre.

There are two wonderful tributes to Chico Buarque—Tatuaggio and Occhi negli occhi—translated by Bardotti, showcasing the Brazilian artist’s ability to turn melancholy into a political act. There are moments when the New Trolls wrap Vanoni’s voice with almost cerebral vocal structures. And then there’s Ti voglio: six minutes of mischief, strings, falsettos, irony, all dressed in disco music that today seems to anticipate the arrival of Italian electro-pop twenty years later.

The project was released both as a double album and in a single-disc version, as if even then there wasn’t just one way to listen to it. And perhaps that’s still true: it’s an album open to multiple angles, never definitive, never locked into a single interpretation.

The Echo of Avere vent’anni

Adding further complexity to the story of this eccentric album is a cultural short circuit that speaks volumes about Italy in those years. Two tracks from Io dentro – Io fuori—Noi and Ti voglio—appear in the soundtrack of the most censored, cut, and erased film from our collective imagination: Avere vent’anni by Fernando Di Leo.

A film that is a cult object today but was received at the time as something alien, disturbing, indecent. Its protagonists, Lilli Carati and Gloria Guida, travel through a tired, violent Italy, unable to truly look at its future. And within that story of denied freedom, Ornella’s voice arrives like a promise—both naïve and tragic.

It’s a detail almost hidden in her discography, yet it says everything: Vanoni was never an artist of reassurances. Even when she seemed perfectly integrated into the mainstream, she was always one step ahead, further out, more courageous.

Rediscovering Io dentro – Io fuori Today

Listening again to Io dentro – Io fuori means approaching a less obvious, less polished, more vulnerable and audacious Ornella. A Vanoni who doesn’t seek perfection, who isn’t afraid of smudges—because life often hides inside the smudges.

It’s an album that allows us to see her from a different angle: not the impeccable diva, not the popular icon, but the woman who moves through her contradictions without being overwhelmed. A woman who, even in her fragilities, was able to transform everything—pain, joy, falls, rebirths—into a form of beauty.

In recent years Ornella learned to speak of herself with an almost disarming sincerity, as if every memory were a fragment to hand over to the world before it dissolved. She described her life as a complex, harsh, luminous weave, and within those words was the same energy running through this 1977 album: the awareness of having lived everything, felt everything, withheld nothing.

Perhaps this is why Io dentro – Io fuori deserves to be rediscovered today. Because within those songs we find a Vanoni who escapes labels, who plays, risks, dares—and precisely for this reason continues to speak to us. A Vanoni complete, imperfect, magnificent. Reminding us, once again, that Ornella truly was everything—and gave everything back.

Photo credits

CGE, CC BY 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Ulaupo, CC BY 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons